I Got Picked to Lead 40 Engineers

(Why You Need to Choose a Domain)

A few months ago, I led (among other great people) an initiative with 40+ engineers working on one thing across our product for four weeks. If you’ve ever tried to coordinate that many people on anything, you know how this could go. It was chaos at first—unclear ownership, duplicated effort, people stepping on each other’s toes. But we found our way and closed 300+ tickets by the end.

Here’s the thing: I didn’t get this opportunity because I raised my hand at the right moment in a meeting. I got it because I had spent months becoming the person people thought of when the problem came up. When leadership needed someone to run this initiative, my name surfaced naturally. The opportunity came to me.

That’s not luck. That’s what happens when you choose a domain and go deep.

The Visibility Problem No One Talks About

Most senior engineers I talk to share the same frustration: they’re good at their job, they ship solid work, but they feel invisible when it matters. Promotions go to people who seem less capable. Leadership opportunities land on other desks. They’re told to “have more impact” but nobody explains what that actually means.

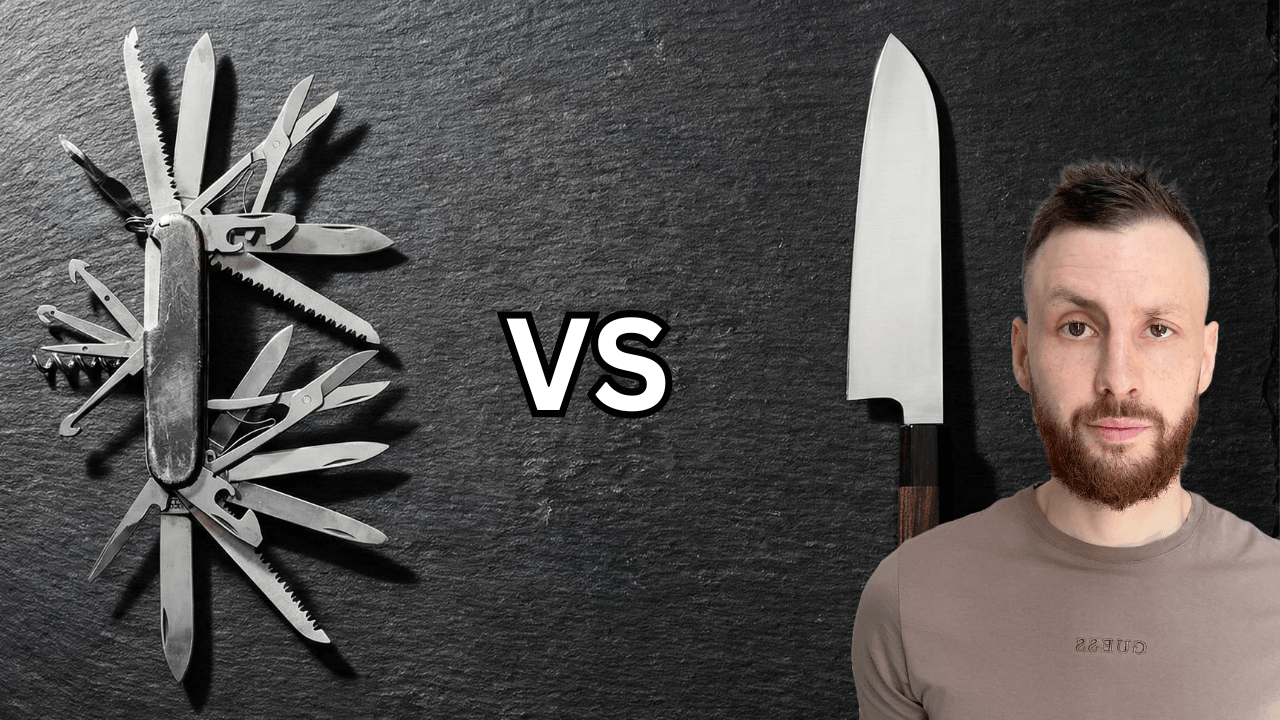

Here’s what I’ve learned the hard way: being a good generalist makes you valuable to your team but invisible to the organization. When you can do a bit of everything, you don’t come to mind for anything specific. And leadership opportunities are always specific. Nobody says “we need someone generally competent to lead this.” They say “we need someone who really knows authentication” or “we need our performance expert on this.”

Domain expertise is what gets you in the room. It’s the difference between being considered and being overlooked.

How to Actually Evaluate a Domain

Forget generic lists of “good” and “bad” domains. What matters is whether a domain works at YOUR company, for YOUR situation. Here’s how to actually figure that out.

Step 1: Find out what leadership actually funds, not what they say they care about.

Every company says they care about security, performance, accessibility, developer experience. Words are cheap. Look at where money and headcount go. Check recent job postings—what roles are they hiring for? Look at the last few promotions to staff level—what were those people known for? Read the company OKRs if you have access. If you don’t, ask your manager directly: “What are the engineering org’s top priorities this year?”

Step 2: Check if it connects to your actual work.

The best domain is one you’ll encounter naturally in your job. If you’re on a payments team, “API security” makes sense—you’ll get real problems to solve. “Kubernetes optimization” might be interesting, but if you never touch infrastructure, you’re building expertise in a vacuum.

Step 3: Be honest about interest.

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: if you pick a domain purely for strategic reasons but find it boring, you’ll quit within a year. I’ve done this. The investment felt like a chore and I stopped.

You need at least moderate genuine interest. Not passion—that’s too high a bar. But enough curiosity that reading about it on a Saturday morning doesn’t feel like punishment.

What if no “good” domain interests you?

This is more common than people admit. A few options:

Try smaller bets first. Spend a month going slightly deeper on three different areas. See which one you find yourself thinking about outside work hours. That’s data.

Look for adjacent domains. Maybe “security” sounds dry but “secure API design” connects to work you already enjoy.

Consider whether this company is right for you. If nothing your company values interests you, that’s a signal worth paying attention to.

The Actual Time Investment (Honestly)

Let me be specific, including the parts that are hard to hear.

You need 2-3 hours per week, sustained over 1+ year. That’s real time that has to come from somewhere.

Where the hours actually come from:

For me, it was: one hour three mornings a week before work, plus some reading during lunch, plus occasional deeper work on weekend mornings when my schedule allowed it. I cut back on Twitter scrolling and random YouTube videos. I watched less TV. I said no to some social things.

I’m not going to pretend this is easy or that everyone can do it. If you have young kids, health issues, caregiving responsibilities, or you’re already stretched thin—four hours might be impossible. That’s real.

The minimum viable version:

If 4 hours is unrealistic, 1 hour can still work—it just takes longer. The key word is consistently. Two hours every week beats five hours for three weeks then nothing for two months.

What those hours actually look like, concretely:

Months 1-3: Mostly reading and watching. Find the 3-5 best books or resources in your domain. Follow the top people on Twitter/LinkedIn. Read their blogs. Watch their conference talks. You’re building mental models. One hour might be: read two blog posts, take notes on what you learned, write down one question you still have.

Months 4-6: Start doing. Take what you learned and apply it to your codebase. If it’s performance, profile something. If it’s accessibility, audit a feature. If it’s security, review a PR specifically for vulnerabilities. Document what you find, even if just for yourself.

Months 7-12: Start sharing. Write your first internal document. Give a 15-minute presentation to your team. Answer questions in Slack when they come up in your domain. You’re transitioning from student to contributor.

Year 2: Lead small things. Propose a working group. Write an RFC. Run a training session. Take on a domain-specific project.

Year 3+: Lead bigger things. Shape standards. Get pulled into planning conversations.

How to protect the time when work gets busy:

You won’t always protect it. Some weeks, work wins. The goal is to not let “some weeks” become “every week.” I treat my domain time like a recurring meeting—it’s on my calendar, it’s blocked. When I skip it, I notice and get back to it the next week. Streaks matter less than not quitting entirely.

Finding Opportunities

The generic advice is “be visible.” Here’s what that actually looks like in practice.

Slack/communication tactics:

Monitor 2-3 channels where your domain comes up. When someone asks a question you can answer, answer it—but don’t be first every time. If you answer every question within 30 seconds, you look like you’re camping the channel for visibility. Once or twice a week is enough to build a reputation without seeming desperate.

When you answer, be useful, not showy. “Here’s the solution: [link]. Let me know if it doesn’t work” beats a five-paragraph explanation of everything you know about the topic.

What “volunteer for unglamorous work” actually looks like:

When someone says “we should really document our authentication flow” in a meeting, and there’s a silence—that’s your moment. Say “I can take a first pass at that.” It’s not exciting work. Nobody will promote you for writing docs. But now you’ve done domain work that’s visible, you’ve demonstrated expertise, and you’ve helped someone. That person remembers.

Other examples: reviewing a spec for security issues, helping interview candidates in your domain, investigating a bug related to your area that’s been sitting unassigned, running a small lunch-and-learn.

Building relationships remotely (specific tactics):

Identify 2-3 people who work in or around your domain. Not random people—people whose work intersects with your area. The security-focused person on the platform team. The tech lead who cares about performance.

Reach out with something specific and low-commitment: “Hey, I saw your PR on [thing], had a question about the approach—do you have 15 minutes sometime?” or “I’m trying to learn more about how we handle [X], heard you’re the person to talk to.”

One 30-minute conversation per month with someone new in your domain’s orbit. That’s 12 relationships a year. After two years, you know everyone relevant.

How to know if you’re being helpful vs. annoying:

Helpful: responding when asked, offering specific assistance, sharing relevant things occasionally (”thought you might find this useful”), being easy to work with.

Annoying: commenting on everything, CC’ing yourself onto threads unnecessarily, giving unsolicited opinions constantly, making every conversation about your expertise, following up when people don’t respond.

The test: are people coming to you, or are you always going to them? Early on, you go to them. By year two, it should start reversing. If it’s not, recalibrate.

The Politics

Expertise opens doors. But I’ve seen engineers with real expertise get passed over because they ignored everything else. Here’s the stuff that actually matters.

Making sure your manager knows what you’re building:

Don’t assume they’re paying attention. They have 6-10 other people to worry about. Every 1:1, I mention one domain-related thing I did that week. Not bragging—just informing. “I wrote up that authentication doc, got some good feedback.” “Helped the mobile team with an accessibility question.” Consistent small updates beat occasional big announcements.

If your manager doesn’t value your domain, you have a problem. Either educate them on why it matters (connect it to team/company goals), find projects that combine your domain with things they do care about, or accept that you might need a different manager to fully benefit from this path.

Building skip-level visibility without being weird about it:

Your skip-level should know your name and vaguely what you’re known for. That’s it—you don’t need a deep relationship.

How to get there: present something at a broader team meeting (your manager can nominate you), write a document good enough that it gets shared upward, work on a cross-team project where skip-levels are involved. Don’t request skip-level 1:1s to “talk about your career” unless your company culture encourages this—at most places, it looks like you’re going around your manager.

When someone else gets credit for your work:

This will happen. Some engineer will present “their” ideas that came from your document, or a project you shaped will get attributed to whoever had the most visible role.

Small instances: let it go. Your reputation builds over time, and pettiness about credit damages it more than occasionally losing credit.

Pattern of someone systematically taking credit: address it directly with that person first, then with your manager if it continues. Keep receipts—documents with your name on them, Slack threads with timestamps.

The best protection is volume. If you’re consistently producing domain expertise, the occasional stolen credit doesn’t define you.

Checkpoints (And What to Do If You’re Behind)

6 months: People on your immediate team come to you with domain questions. You’ve written at least one internal document.

If you’re not there: You’re probably not being visible enough. You might be learning but not sharing. Write something, present something, answer more questions publicly.

1 year: People outside your team know your focus. You get pulled into relevant conversations—architecture reviews, interviews, incidents.

If you’re not there: Either visibility problem (you’re not sharing enough outside your team) or domain problem (you picked something your company doesn’t actually care about). Ask your manager: “Am I becoming known for anything specific?” Their answer tells you a lot.

2 years: You’re leading domain-specific work. People you’ve never worked with reach out.

If you’re not there: Have you actually tried to lead something? Sometimes engineers wait to be asked. Propose something. Also possible: your company has a ceiling for your domain and you’ve hit it. Time to expand scope or consider whether this company is the right place to continue growing.

3+ years: You shape strategy. Opportunities come to you.

If you’re not there: Likely a politics or scope issue rather than expertise issue. You might have the expertise but lack the relationships or trust with leadership. Or your domain might be seen as “important but not strategic.” This is where some engineers hit a wall and need to either expand their domain, get more involved in business-level conversations, or move somewhere that values their expertise more.

When Your Domain Bet Doesn’t Work Out

Let’s be honest: sometimes you spend 1-2 years on something and it doesn’t pay off. Your company pivots, leadership changes, the technology shifts, or you just picked wrong.

This sucks. There’s no way around the sunk cost feeling. You will be frustrated and wonder if you wasted your time.

How to know when to quit vs. push through:

Quit if: your company has clearly deprioritized this area (budget cuts, layoffs in that domain, leadership saying different things now), you’ve given it 12+ months and you’re not hitting even early checkpoints despite consistent effort, you’ve lost all interest and it’s affecting your overall motivation.

Push through if: you’re making progress but it’s slower than you hoped, you still have genuine interest, there are signs the company might re-prioritize this area.

How to pivot:

Look for bridges to adjacent domains. If you spent two years on performance and it’s not valued, “cost optimization” might be—and uses much of the same expertise. If security isn’t landing, developer experience around secure defaults might.

The meta-skills transfer completely. You know how to go deep, how to build visibility, how to lead domain initiatives. That’s the hard part. Applying it to a new domain is just repetition.

The real cost:

I won’t pretend a failed domain bet is costless. It’s 1-2 years where you could have built expertise in something that did work. That’s real. But here’s the alternative: staying a generalist forever, never betting on anything, and remaining invisible. That’s a bigger loss—it’s just a slower, less visible one.

This Path Works for ICs Too

Quick note because people assume this is about becoming a manager: it’s not.

Staff and principal engineers are almost always domain experts. That’s how you get the credibility to make technical decisions that stick, to influence architecture, to operate at an org-wide level without managing people.

If you want to stay technical, this path is arguably more important than if you want to manage. The IC track has fewer positions and requires sharper differentiation. Domain expertise is how you get it.

P.S. I help senior engineers become tech leads through 1-1 coaching.

👉 Apply here if you’re ready to build this muscle.